Estimating a Project to See If You Want to Do-It-Yourself

For most homeowners, the urge to “do it yourself” comes from a desire to save money. While some people are craftsmen and want to put something of themselves into the project, most are hard-pressed to do any of their own repair work. If you approach the job as a Project Manager, your chances of success are improved.

You may not know how to do a project, but some things are worth trying if you have the time and the energy. Some things are definitely not worth doing yourself unless you are already know something about it. If you tackle something beyond your ability, the result could actually make things worse, or at least cost more than the original bid to correct.

Do you have the time? Are you healthy? (a sprained ankle from a skiing trip will slow you down for a while.) Is bad weather coming soon? These things will all affect how you feel about a “do-it-yourself” project at any given time.

Deciding how to approach a project requires a clear understanding of what is involved. If you are planning to hire someone, you should have some grasp of the magnitude of the job. (Even skyscraper construction projects can be broken down into manageable components!) Let’s look at how to assess a job.

Accurate Estimating Is the Key to Success

The first thing most people want to know is how much money they will save by doing the work themselves. If the job is mostly labor and you have the skill, you may be able to save quite a bit. However, a professional may be able to get better prices on materials, have the right equipment already on hand, and do a better-looking job. Painting is one of the jobs that people often do themselves, but the results vary widely according to the knowledge and effort put into the job. Do a little homework before you make a final decision about doing a job yourself.

Small Jobs

Practice your project management skills by trying small jobs. You can create a simple estimating matrix to get started. The cost can be split into categories, and the categories estimated individually. The four categories you will set up for replacing a fence include Labor, Material, Equipment, and Subcontractors.

• Labor represents the work of others when you pay them by-the-hour and you are responsible for what they do.

• Material includes all the parts that you must buy to use in the project, including fasteners, clean-up supplies, etc.

• Equipment includes tools that must be rented or purchased, such as paint sprayers, tractors or excavators.

• Subcontractors are the people who provide everything you need for a portion of the project and are completely responsible for that part. A subcontractor gives you a bid that includes material and labor, and directs and supervises the persons doing the work.

Example: Building a Fence

Suppose your back fence blew down in a windstorm. You need to get the fence replaced soon, but you are short on cash and think you might save some money if you do it yourself. How much will you save?

First you go out and measure the place where the fence will go–we’ll say it’s fifty feet. We will assume that none of it is salvageable and that you can’t get your neighbor to contribute. You decide to replace it with six-foot-high cedar fence boards. You look up “Contractors–Fence” online for your region and get prices starting at $20 per foot. This is a total job cost of $1000. Now you want to figure what it would cost you if you did it yourself.

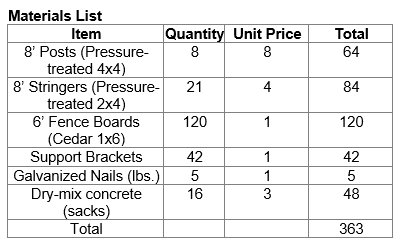

You will provide your own labor, and you’re not sure how long it will take, so let’s start with estimating the material. Most fences have one post every eight feet (measured from center to center), so you will need seven posts, except that you will be short two feet. If you stretch the distance between the posts to make up the two feet, you can’t use 8’ two-by-fours between the posts (stringers), so you’d better get eight posts. These will be eight-foot-long four-by-fours (4” x 4” is really 3 ½” x 3 ½” if you buy lumber that has been milled to a smooth finish).

You will want three stringers between each post, so that’s three times seven, or twenty-one cedar two-by-fours. You also want 50 lineal feet of fence boards, which are probably one-by-sixes (actually 5.5”), so you will need at least 110 boards. Unless you can hand-select these, you will need a few extras to be sure you have enough good ones, so let’s say you need 120 boards. If you use galvanized brackets to secure your stringers, you need two per board (42 brackets). You also need galvanized nails in two sizes; small ones to secure the stringers to the brackets and larger ones to nail the fence boards to the stringers. If you decide to cement the posts, you will need a couple of bags of ready-mix for each post (2 x 8 = 16). How is our material list shaping up now?

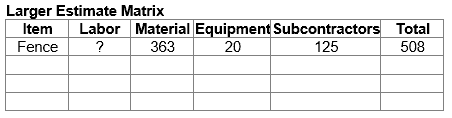

You now have a material total for your job. This assumes that you are not painting the fence after it is finished. You don’t have a pickup truck, but the lumber store will deliver, so you keep going. Since you have no way to get rid of the old fence, you subcontract that job. This person uses his own vehicle, and agrees to haul it away for a flat fee of $125. This goes in the “Subcontractor” column. You own a shovel, a saw, a hammer, and a level, but you need to rent a post-hole digger (the “clam-shell” type, not a powered one) and a wheelbarrow. This costs $20 for one day. (You had better plan your time well, or that cost will double!) This amount goes in the “Equipment”” column. So far, you figure the fence will cost you over $500 plus your labor, so your time is worth less than $500.

You won’t know what this represents as an hourly rate until you do the job, but you can begin to speculate. Odds are the job will take longer than you think it will. Your hourly rate will probably be between $10 and $20 per hour, assuming you finish the job. Don’t forget the aggravation factor. This is hard work, and your hands may get blisters. Your shoulders will ache, and if you don’t finish on schedule other aspects of your life may suffer. It’s easy to underestimate time and materials. If you decide to “do-it-yourself” to save $500, and in the end find that you only saved $300 and were miserable the whole time, it may not be worth it. If you successfully saved $500, enjoyed the project as a change of pace from your desk job, and beam with pride every time you look at the fence now that it’s done, you made the right decision.

The more you can identify the “hidden” costs of a job, such as sealants, clean-up supplies, additional impulse purchases when you are at the home improvement store, and extra trips to the lumber yard because you forgot something, the better choice you will make in deciding what to do yourself. Project Managers usually include a “contingency factor” in their estimates as a cushion when preparing a bid, just in case they forgot something or find an unexpected problem on the job.

Compare DIY with Hiring a Professional

How much do you think a contractor should add to his bid to allow for the time that the homeowner spends distracting his workers with questions and chit-chat? How much should be added to cover the tool that breaks down in the middle of the job, and has to be taken in for repairs before the job can be finished? These are some of the factors that cause contractors to come up with different bids for the same job, and why at first glance bids often seem to be high.

Contractors need to make a living, and if they bid too low they risk actually losing money. Contractors must also cover their overhead, including office supplies and forms, insurance costs, vehicle maintenance, tool replacement, clerical staff, payroll taxes, and all the other costs of doing business. (If you DIY you won’t have those costs.)

The contractor also spends a lot of time on your job that you don’t see, such as preparing the estimate, calling subcontractors, picking up materials, etc. A client who fails to recognize these legitimate costs of doing business may feel like he is somehow being cheated.

Ironically, a well-organized and efficient contractor can make the job look almost easy, while a poor contractor will seem to be working harder because he is always dealing with problems. If your job is half-way completed and things have not been going well, you would be more than ready to “pay extra” to have avoided the unnecessary hassles.

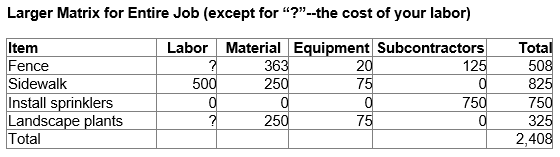

If you are the Project Manager you may hire contractor(s) for the whole job–especially if there are other tasks to be done besides replacing a fence. If you pick a good contractor at the beginning you can avoid a lot of problems, even if the bid was not the lowest one you received. Now that you are aware of some of the many things that can affect a bid, we can return to our sample estimate. The fence-building example above may represent only one part of a larger job. You can fill in a larger matrix with a separate line for each trade or specialty.

Any system that allows you to include everything in your estimate is going to give you a good roadmap to your project. This is the “bottom line” that causes contractors to sink or swim–it is critical to include all the costs, because once you start you need to be able to afford to finish!

A good estimate gives you a roadmap for making decisions–DIY or hire a professional? How much time will it take? What is your time worth? Do you have the time, even if you DO want to save money? When you visualize each step of the job to make an estimate it will help you decide who should do each step and how long it might take. The tools of the Project Manager are the description of the job, the cost to complete, and the schedule for making it happen. A good estimate brings these into focus.

Be sure to evaluate your project when it is complete. Was it worth it to do it yourself? The answer may still be yes if the job turns out okay and you saved a fair amount of money. The important thing is to know what you are getting into before you decide. It’s even worse if you do-it-yourself and realize after the job was done that the unexpected extra costs and hassles resulted in no savings at all. You can read this post to help with “lessons learned.”